In spite of the lack of snow, I found myself pondering the phenomenon of Alaskan Winter while out walking the dogs this morning. Without a doubt, winter survival is the number one topic raised by Outsiders (non-Alaskans) when they find out where I'm from.

What I've realized over the years, however, is that it is the darkness rather than the cold which holds the mystery, perhaps mingled with a soupçon of fear. But I guess most people have experienced winter cold and snow at some point in their lives, even if only on a weekend ski trip. The perception of round-the-clock darkness, however, is another matter.

Before moving to Alaska, I spent six years living in Wisconsin -- not even northern Wisconsin, but the southern part of the state, down in Milwaukee and Madison. Nevertheless, I probably experienced some of my most brutal winter days living there. Wisconsin winters are like a dirty barroom brawler: they're out to inflict pain from the outset, and with bitter winds and occasional rain, they're poised to do just that.

In contrast, Alaskan winters are more like an elephant that comes into your home at the end of October, slowly sits down on you, and then simply refuses to budge before about mid-April.

And, yes, it is dark for most of each day. But even as a little girl growing up in Ohio, I remember going to school in the morning ... and it was dark. Then coming home late afternoon... and it was getting dark. And, in Anchorage, on Winter Solstice, December 21 (the shortest day of the year no matter where you live in the northern hemisphere), it's never completely dark -- it's at least sort of dusky [sorry, I can no longer say the word "twilight" without thinking of sparkly teen vampires -- thanks a lot, Stephenie Whatserface].

[Quick note of Disclaimer: As you probably know, Alaska is a big state. In case you haven't seen this graphic, here's the upshot:

In the state of Alaska, I have lived only as far north as Fairbanks, which has shorter winter days than Anchorage but still has at least four hours a day of winter light. Cities such as Barrow, in northern Alaska, do have still shorter winter days. However, since I have no personal experience living that far north, this post pertains primarily to Anchorage and, a little less so, to Fairbanks.]

Nevertheless, popular perception remains that, somewhere around September, someone throws a big light switch in the sky, and Alaska is plunged into total darkness for six months.

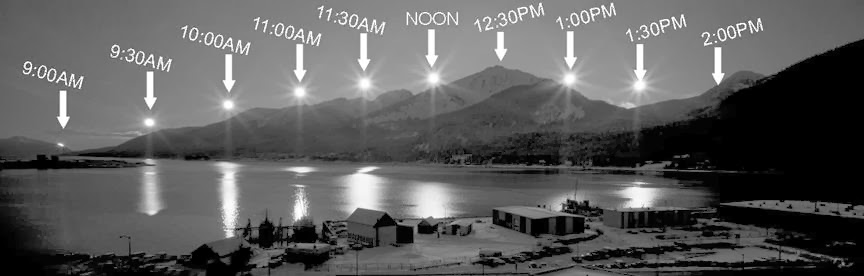

So, to correct the misconception, here are some (hopefully) helpful diagrams:

OK, these first two diagrams show the sun's position in the sky at three different times of the year (summer solstice/June 21; vernal or autumnal equinox/March or September 21, respectively; and winter solstice/December 21) at two different latitudes: Arctic circle (first diagram) and Equator (second diagram).

If you live on the equator, the sun rises due east, to a point directly above your head at noon, then sets due west. The farther north you move away from the equator, the more the sun sort of skirts along at an angle in the sky; it's never directly overhead, not even at high noon on Summer Solstice. The upper diagram of the Arctic Circle (66 degrees Latitude) does a nice job of showing how, in winter, the sun still comes up and moves across the sky, just not as high:

|

| (Taken in Juneau, Alaska [Latitude 58 degrees North], on Winter Solstice) |

Similarly, in summer, the sun's path doesn't allow its lowest point to drop off the horizon. Which is why summer's midnight hours look something like this, in time-lapse:

OK, so what does this mean in real life?

Well, here we are in November, about six weeks away from Solstice, and this is what my sunny neighborhood looked like today around noon:

So, as you can see, there's plenty of light and sun -- though the sun can't really be described as "warming" at this time of year -- but it's low in the sky, even at noon, and casting long shadows.

In my house, the light looks like this:

OK, so my dogs are a little spoiled. What can I say? They make me happy, so I'm willing to move their dog beds several times a day so their sunbathing remains uninterrupted. This time of year, the beds are halfway into the kitchen because the sun's rays are so low -- In summer, the beds are right up against the sofa at the front of the house.

Making more sense now? Like I said, I'm not really sure why it bothers me that Outsiders sometimes have difficulty grasping this concept. I think, for me, part of it is because the quality of winter light in Alaska is so beautiful, it's unlike anything I've ever seen before. Maybe it's because the sun is closer to the Earth that the light so brilliantly illuminates everything in its path, turning even mundane objects into works of art:

So next time I'm talking to an Outsider, and a dreamy look crosses my face when they say, "Alaska?!? But it's so cold! And dark!!! Aren't the winters just awful??," it's because this is the image in my mind:

... and I reply, "No, they're actually quite lovely."

No comments:

Post a Comment